George Avery

In 1865, George Avery was a 19-year-old blacksmith enslaved by the McDowell family. It is likely he was born in to slavery, given his young age.

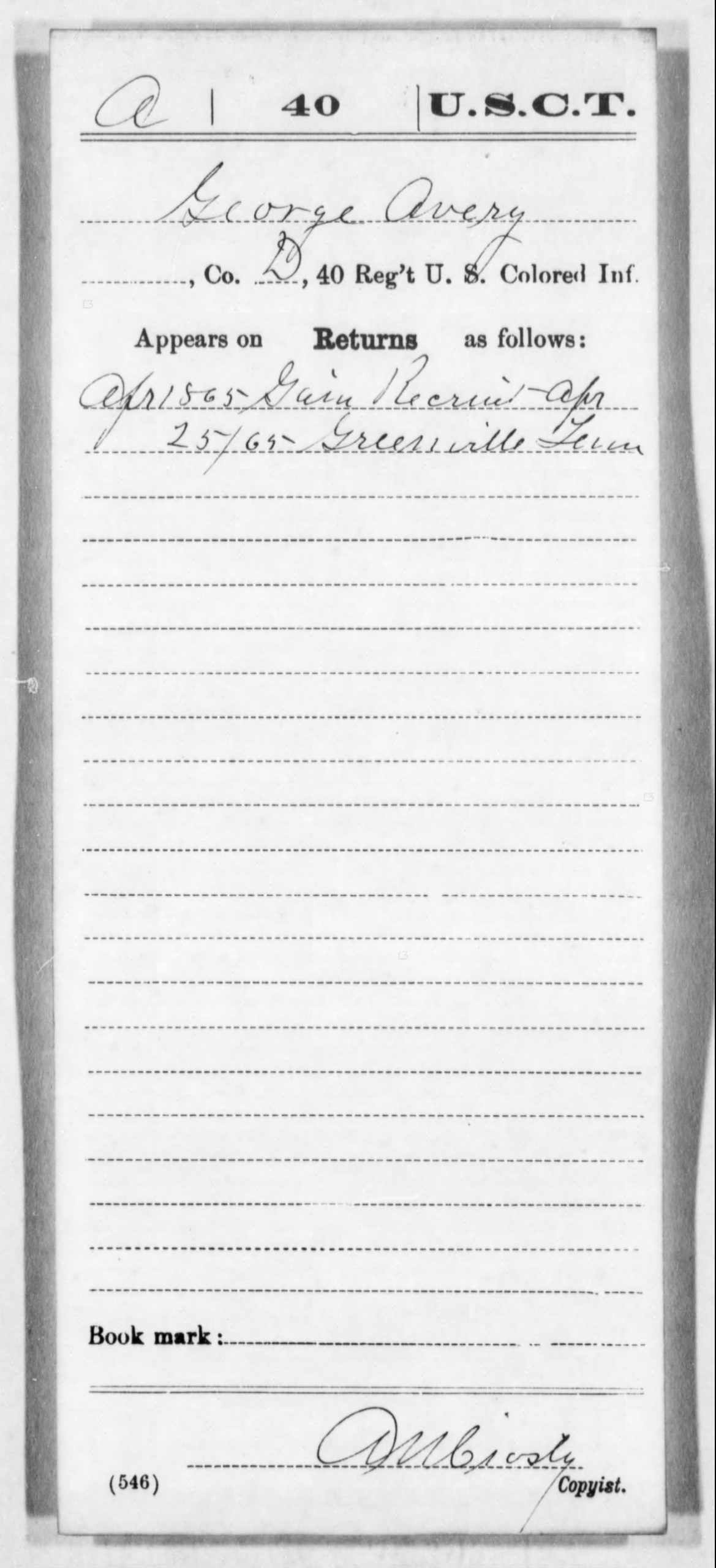

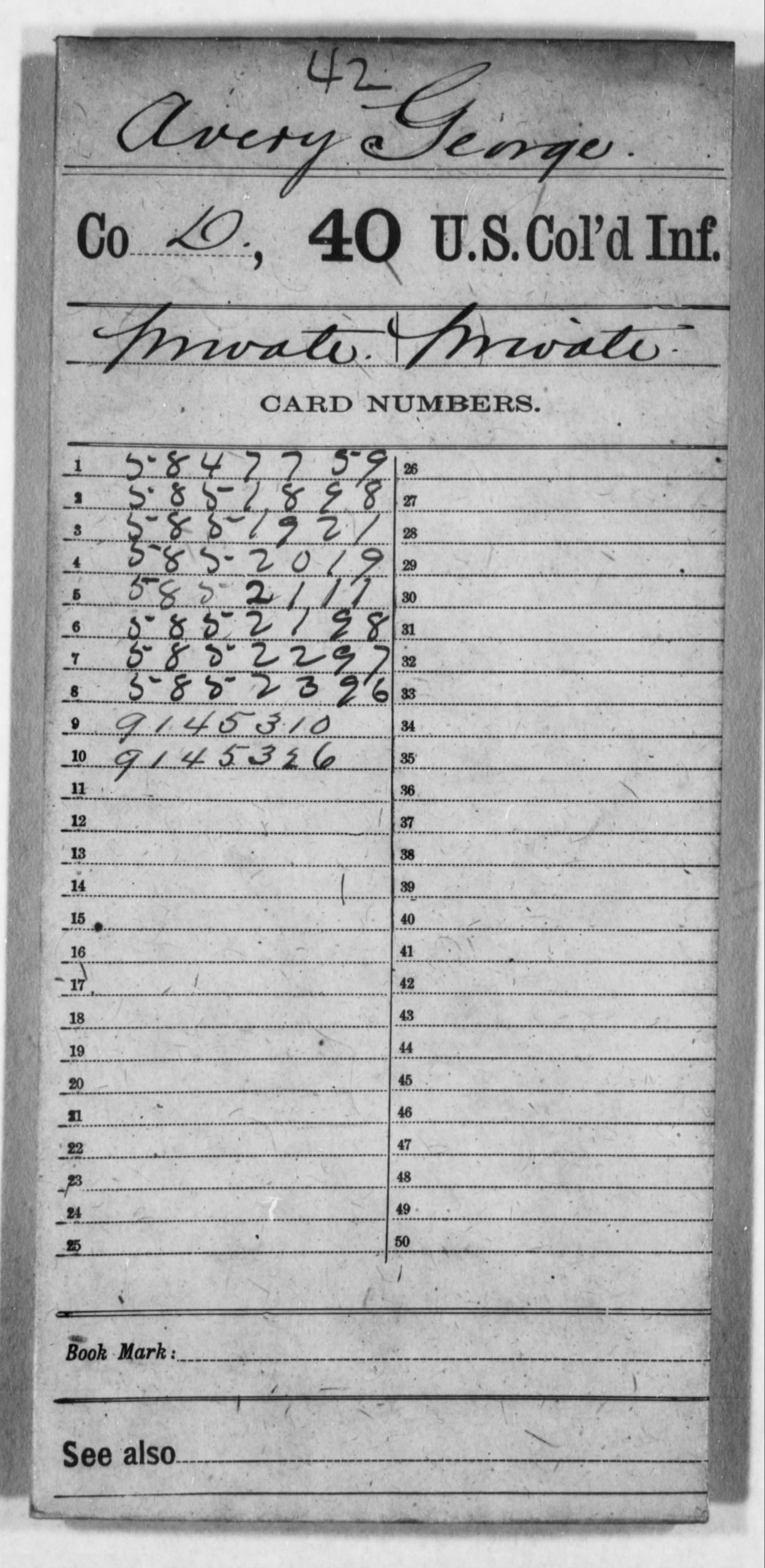

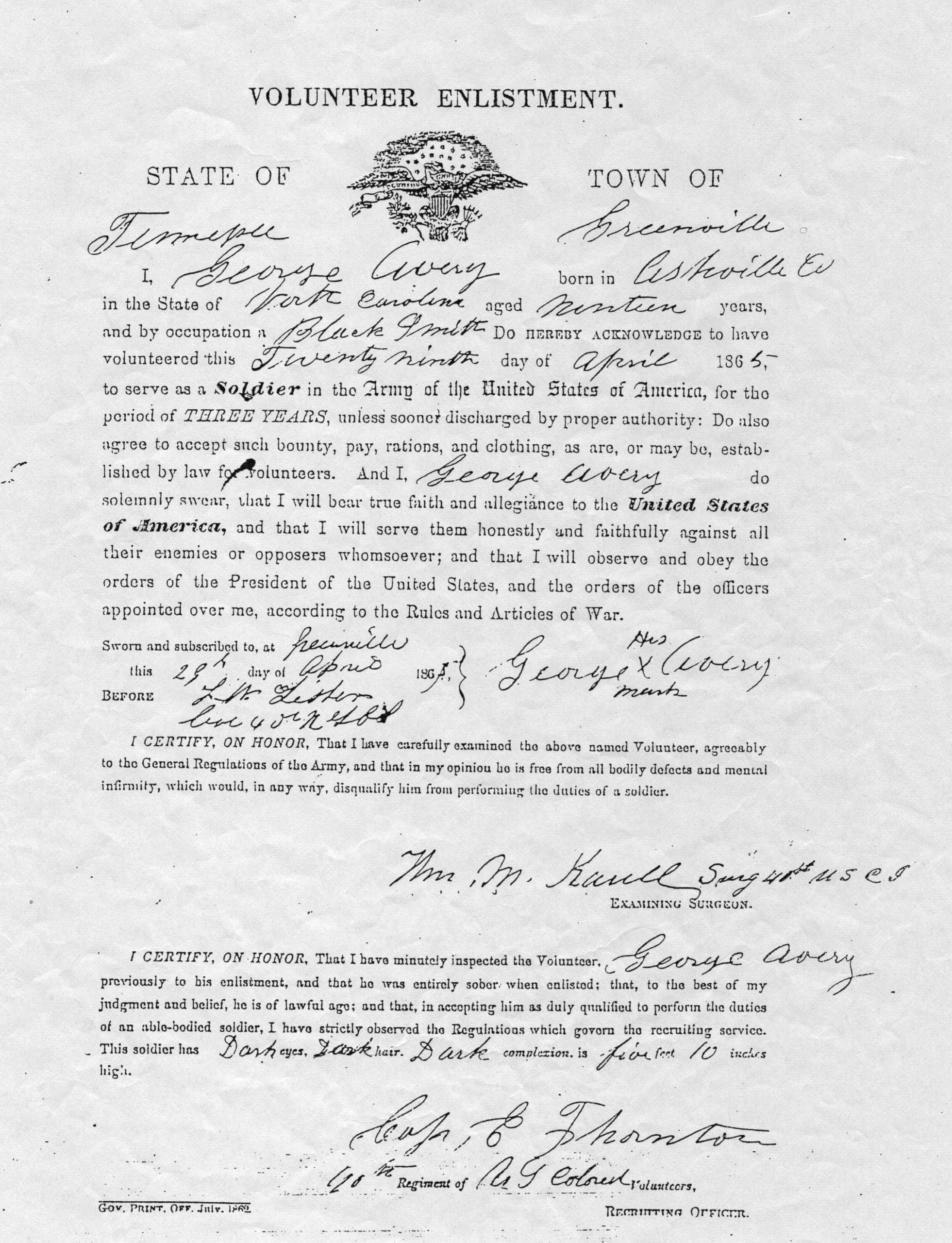

McDowell family stories say that George was freed by William McDowell in April 1865, who realized the Confederacy was going to fall. McDowell allegedly advised Avery to join the Union Army so that he could claim a pension. However, we also know that 40 ex-slaves joined the liberating army when they left Asheville and marched to Greeneville, TN, and it is likely that George Avery was one of these men. George joined the Company D, 40 Division, US Colored Troops, on April 29, 1865 in Greenville, TN, and signed his volunteer enlistment papers with an “X”.

On his return from the war one year later, the McDowells are said to have given him land and lumber with which to build a house and a job as caretaker of the South Asheville Cemetery on Dalton Street. However, based on land deeds registered with the Buncombe County Register of Deeds, it appears that George Avery was not given legal title to any of the McDowells’ land until 1890, at which time he paid $120 for a small tract.

The cemetery, which was also located on land owned by the McDowells, was first used as a burial place for the people they and their families enslaved. Avery dug graves at the cost of $1 to the family of the deceased and looked after the site until his own death in 1938 at the age of 94.

Nearly 2,000 graves have been identified at the cemetery, but most are marked with field stones and, likely because George was never given the opportunity to learn to read or write, he kept all the details about burials in his head.

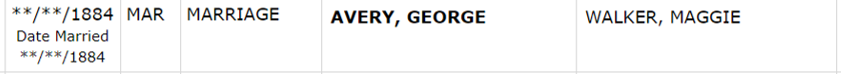

George married twice. His married his first wife, Maggie Walker, in 1884. Maggie passed away in 1913 and was buried in the South Asheville Cemetery. In 1914, he married Bessie McAver/Weaver and – at nearly 70 years old, became stepfather to her two young children.

George Avery died in 1938 and was also buried in the South Asheville Cemetery. His grave is marked with an upright military gravestone for his Civil War service.

Primary Sources

George Avery was born c1845. Avery’s death certificate from 1938 does not list a birth date nor a name for his mother or father. It does, however, list an age of 94 and a birthplace of Marion, NC.

This coupled with Avery’s enlistment papers (scroll down) in which he reports his age as 19 on April 29, 1865, gives us an approximate birth year of 1845. In this document, however, his place of birth is listed as Asheville, NC.

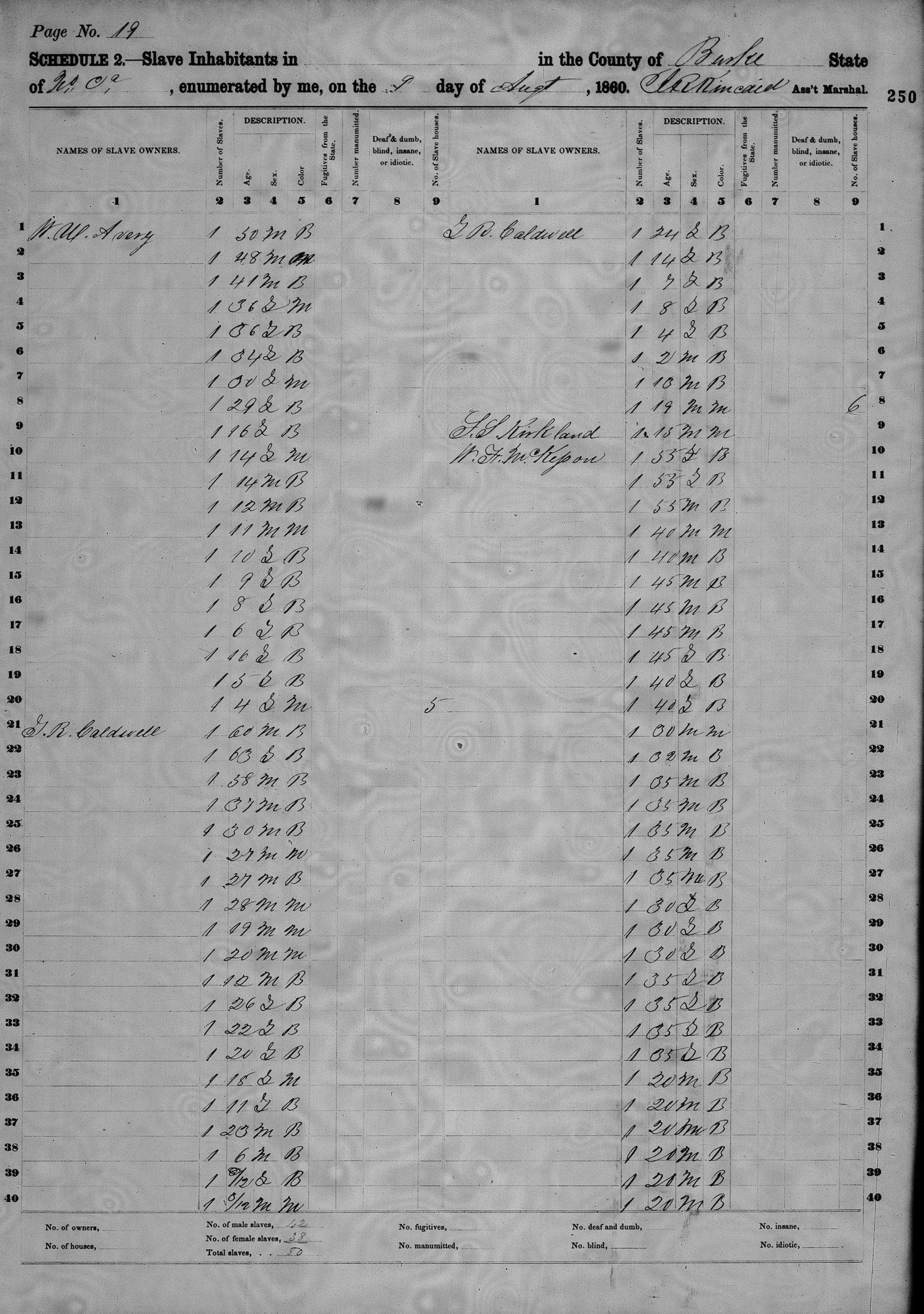

The 1850 Census divided Americans into “Free Inhabitants” and “Slave Inhabitants.” While “Free Inhabitants” were listed by name, “Slave Inhabitants” were only listed under by sex and age under their owners name.

In 1850, William Wallace McDowell owned 11 people, including two 5-year-old males. It is possible that one of these boys was George Avery.

If*, however, George Avery was born in Marion, NC, as it says on his death certificate, he could have been six-year-old male enslaved by William W. Avery in McDowell County, NC, on September 17, 1850.

*W.W. Avery is the only person with the last name Avery listed as a slaveholder in McDowell County (Marion, NC) or Buncombe County (Asheville, NC) in 1850, the two possible locations of George Avery’s birth based on primary documentation.

The possibility that George may have been born on W.W. Avery’s plantation is further supported by an advertisement found in the May 3, 1842 issue of The Raleigh Register.

Though this advertisement appeared before George Avery’s birth it is important to note the relationship between William W. Avery and James McDowell, William Wallace McDowell’s father. William Wallace McDowell was born in 1823 at Pleasant Gardens.

Note: This portion of Burke County became part of McDowell County in 1842.

We have not yet located any written evidence of W.W. McDowell purchasing or inheriting anyone by the name of George.

William McDowell had dramatically increased the number of people he enslaved by 1860. It is possible that George is the 16-year-old male listed on the census.

However, it is also possible that George Avery could have been enslaved by W.W. Avery in Burke County. If so, he could be the 14-year-old male listed on the 1860 census.

It is also possible that George is neither of these people.

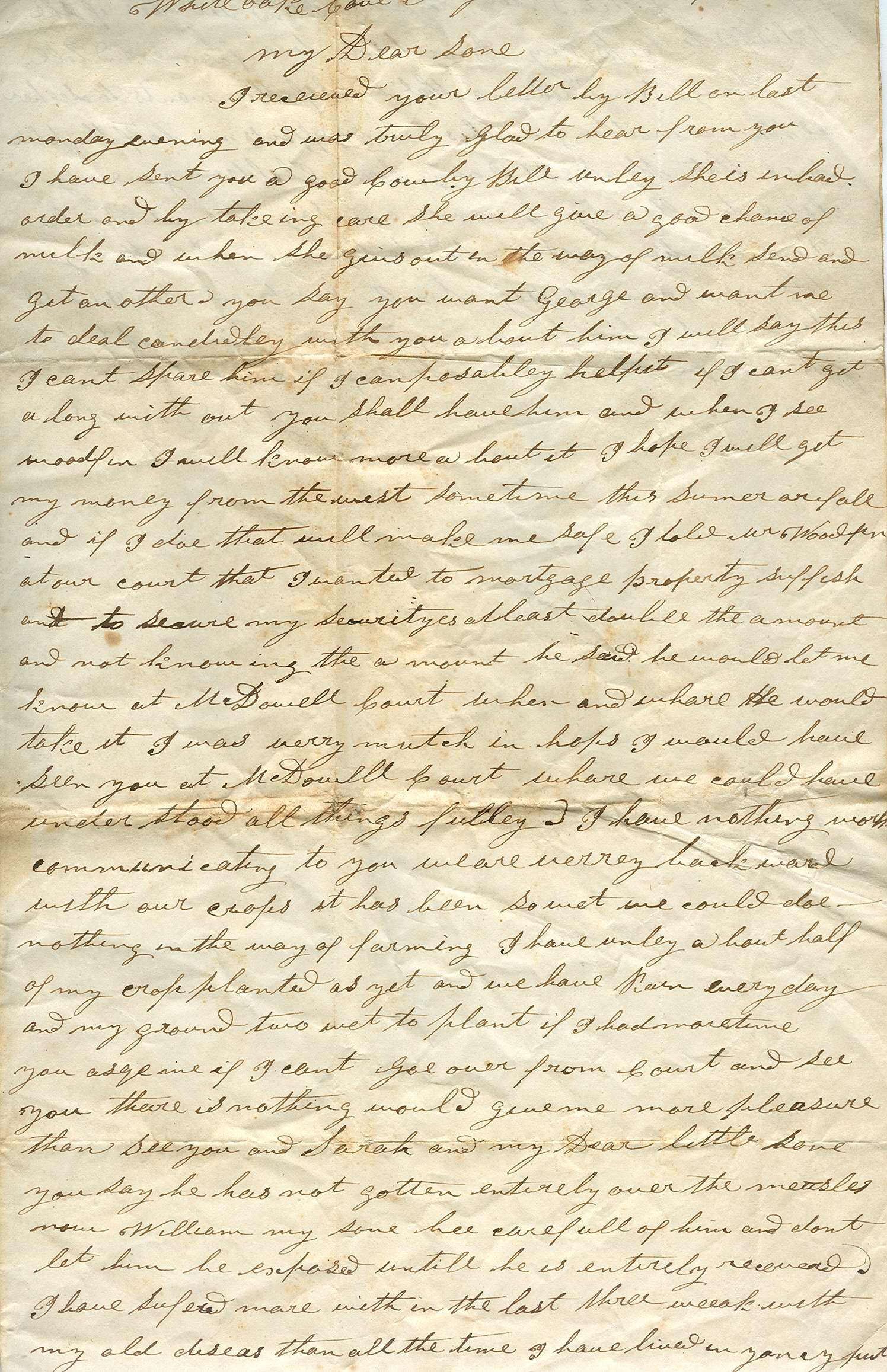

In 1849, James McDowell wrote a letter to his son, William Wallace McDowell, which read, in part:

You say you want George and want me to deal candidley [sic] with you about him. I will say that I can’t spare him, if I can posabley [sic] help it if I can’t get a long with out you shall have him and when I see Woodfin I will know more about it.

At the time this letter was written, James McDowell lived in Yancey County and William McDowell lived in Asheville. George Avery was likely around 5 years old. We have no way of knowing if the George the McDowells are writing about is George Avery. (However, during the census taken the following year, James McDowell enslaves 12 people, including 4 males. Their ages are 51, 36, 16, and 6.)

Regardless, the letter does give us a little insight into William McDowell – who by 1865 did enslave George Avery – and the traumatic uncertainty that people who were enslaved experienced at the hands of their white owners.

Image: Most of page 1 of 2 of letter dated May 2, 1849 from James M. McDowell to his son, William W. McDowell

“A List of Property sold by WW McDowell Adm of Jame McDowell Deceased at the late residence of James McDowell in Yancey County of the 8th day of April 1854 on a credit for and twelve months.”

[Yellow highlights were people were sold.]

The yellow highlight on the left at the bottom of the full documents shows:

“J.A. & J.C. McDowell Dr. to boy George rate 900.00”

Smith-McDowell House Collection

The first confirmed primary documentation we have of George Avery is in April 1865, when George Avery enlists in the Union Army. In this document, Avery reported his age as 19 and his birthplace as Asheville, NC. He was enslaved by the McDowell family at the time.

According to McDowell family tradition, they freed Avery and several other men and encouraged them to enlist, so that they could receive a pension.

The family likely had little choice, however, as around this same time Union General George Stoneman’s troops arrived in Asheville and liberated the enslaved population. They recruited about forty “Negroes who were following the column” and took them to Tennessee. It was in Greenville, TN, that Avery enlisted in Co. D, 40th U.S. Colored Troops on April 29, 1865.

The unit guarded railroads in East Tennessee and was mustered out on April 29, 1866.

After he left the Army, Avery returned to Buncombe County and became superintendent of the South Asheville Cemetery, which had been founded in the early 1800s as the final resting place for people who had been enslaved by the Smith and McDowell families.

From: South Asheville Cemetery.net:

The South Asheville Cemetery’s first known caretaker was an enslaved person named George Avery (1844-1938). Mr. Avery was owned by William Wallace McDowell (1823-1893), who lived in the Smith-McDowell House, and Mr. McDowell entrusted Mr. Avery as the manager of this cemetery, located on the family’s property.

Mr. Avery’s monument is one of only ninety-three headstones that have names or dates identifying the people buried at this site, but the South Asheville Cemetery is a two-acre burial ground that serves as the final resting place for approximately two thousand African Americans.

During the 20th century, the neighborhood surrounding the cemetery would come to be called South Asheville. This area was absorbed into Kenilworth and then, subsequently, into the City of Asheville. African American residents of South Asheville mostly attended two churches, St. John “A” Baptist and St. Mark A.M.E. Church. Over this same time period, the South Asheville Cemetery was one of only a few cemeteries for African Americans in the region, and it is notably the oldest public African American cemetery in western North Carolina.

Part of the South Asheville Cemetery was allotted for church congregants, but any African American community member could be buried in the cemetery for a nominal fee. Many of these people were buried in wicker baskets or pine coffins, their graves marked only by field stones or handmade crosses. Due to the settling of the ground and the array of unusual grave markers, the cemetery must be cleared by hand. The South Asheville Cemetery was closed after the City of Asheville annexed South Asheville and Kenilworth, and the last person interred there was Robert C. Watkins, buried in 1943.

The South Asheville Cemetery fell into disrepair during the mid-twentieth century, but in the 1980s members of the St. John “A” Baptist Church community–most notably George Gibson and George Taylor–began restoration efforts on the property. It was brought back to the public’s attention over this time period when a series of oral history recordings, now housed at the UNC-Asheville Special Collections Library, documented people’s recollections of the cemetery. Over the last thirty years, thousands of volunteers have worked with members of the South Asheville Cemetery Association to improve and maintain this sacred and historical site in an effort to promote greater public awareness of African American history in Buncombe County and to honor the people buried there.

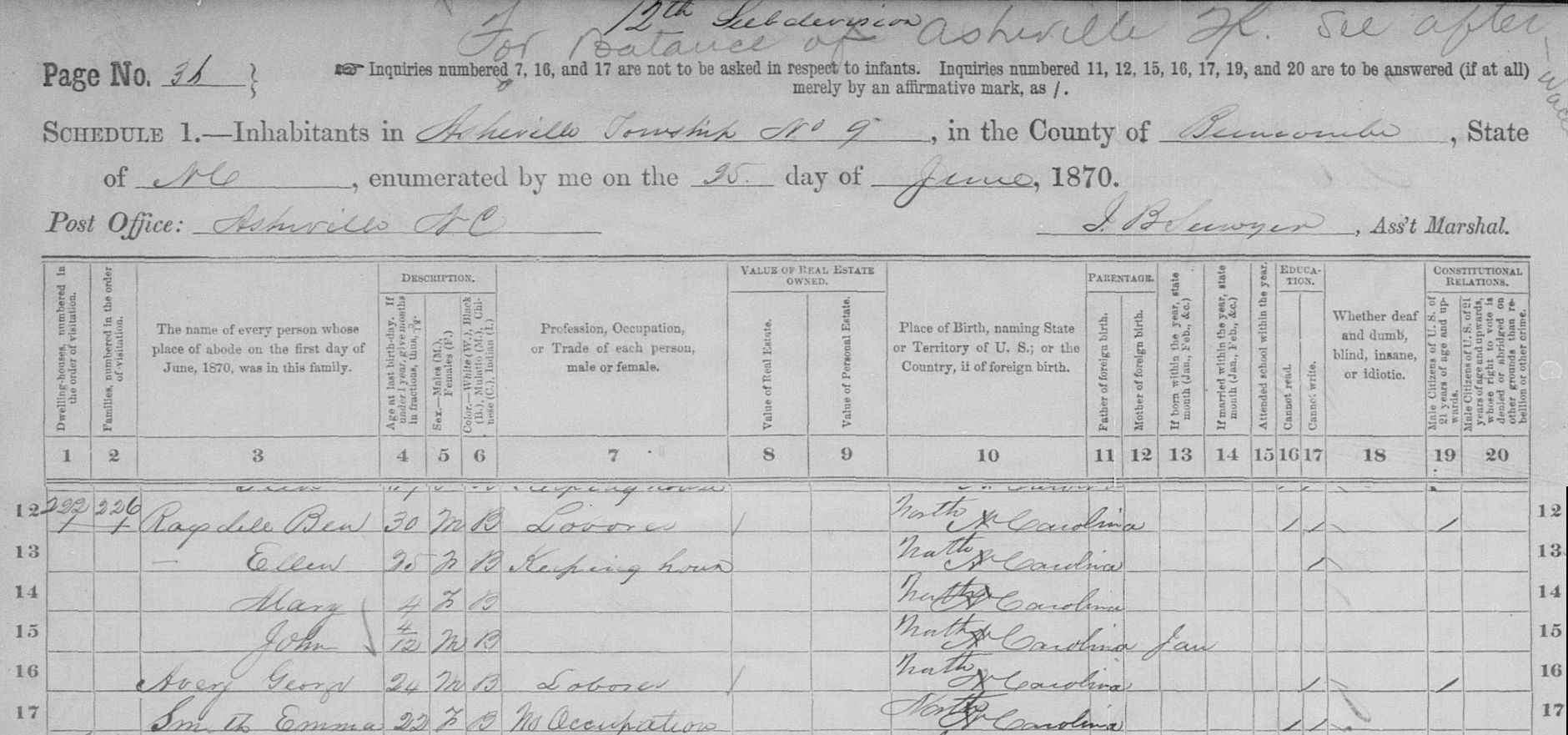

The 1870 US Census was the first which accounted for Black Americans by name in Buncombe County. Here we see Avery listed as 24 years old, single, and working as a “Laborer.” Here, the hash marks indicate that George Avery can read, but not write.

[1870 US Census, Buncombe County, George Avery. Image cropped and spliced to better show column headings.]

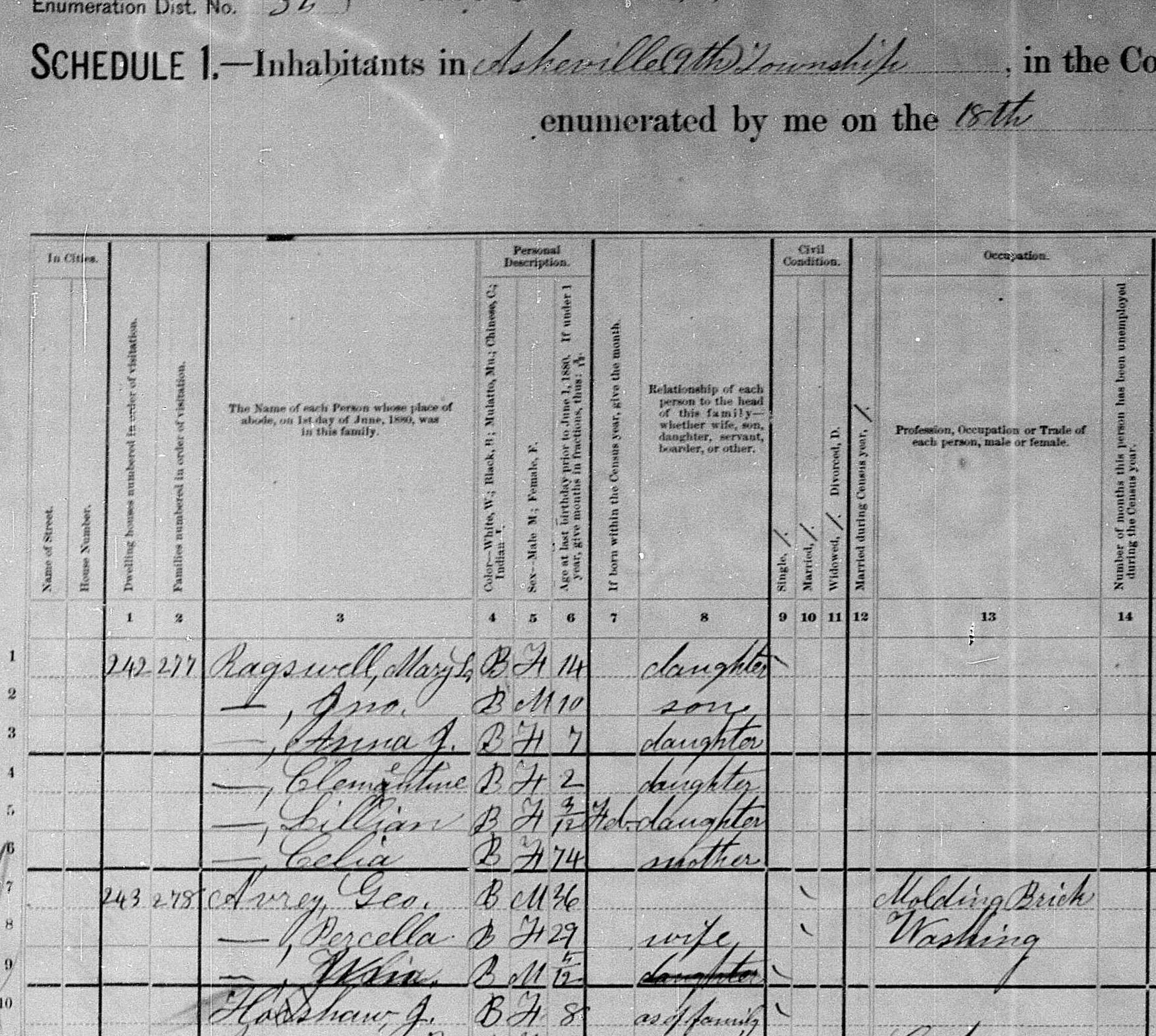

In 1880, George Avery was living with his wife, Percella, next door to the Ragsdale family and working “molding brick”. (Ben Ragsdale had also been enslaved by the McDowells – and George had been living with Ben’s family in 1870.) It appears that Percella passed away between 1880 and 1884.

In 1884, George Avery married Maggie Walker. [Entry from Buncombe County Register of Deeds]

The Buncombe County Register of Deeds has many digitized records relating to land purchased or sold by George Avery. They are complied in a single PDF here.

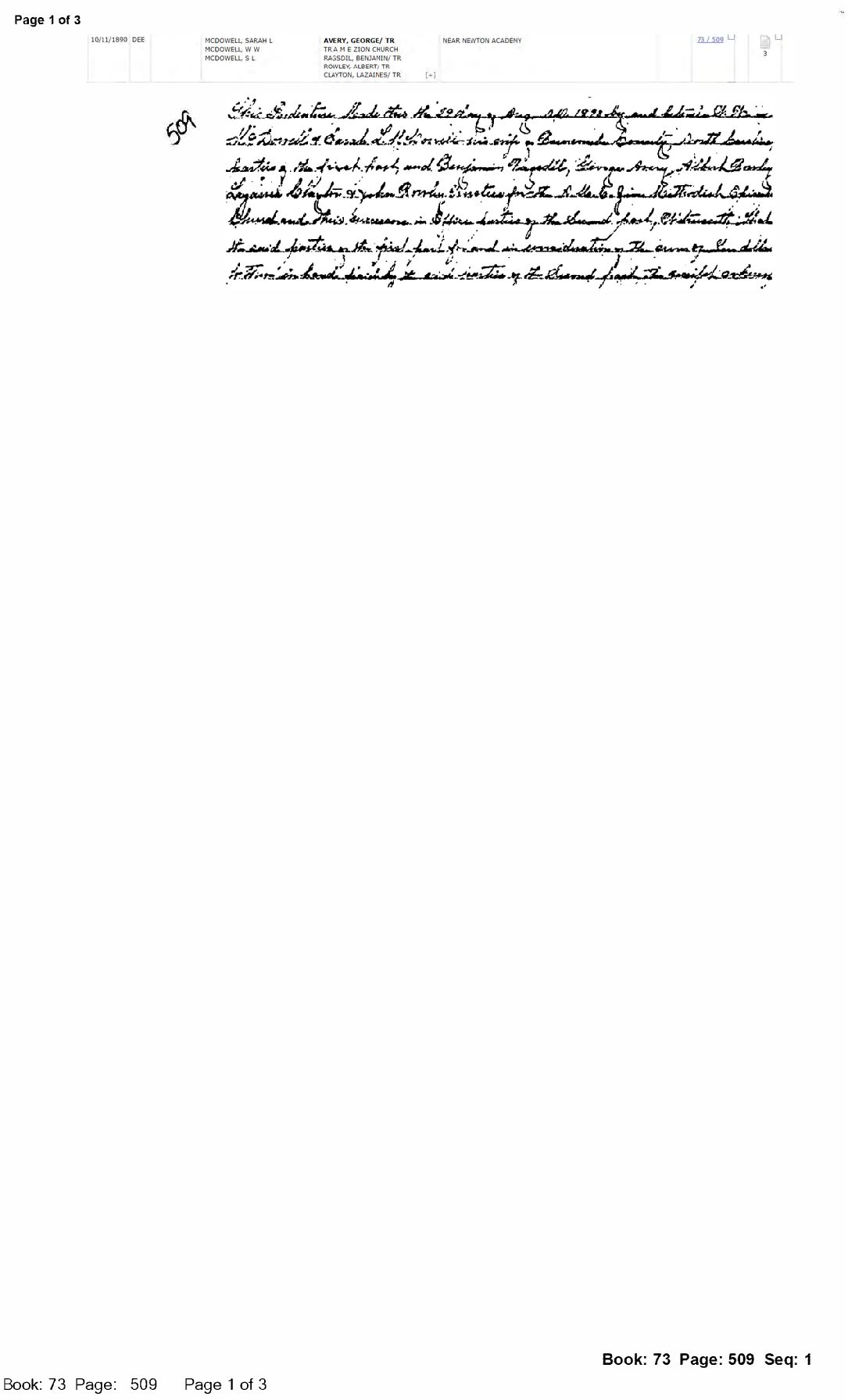

The first deed we see is a transfer of property to George Avery and other men associated with the AME Zion Methodist Episocpal Church from William and Sarah McDowell in 1890. It is very difficult to read; however, on the second page it reads, “…this property to be used as a Cemetery for Colored people and in the event that same is used or appointed for other purposes than Cemetery [illegible] for Col’d people, then the rights, interest, and title is to [revert?] the said W.W. McDowell and his heirs and assigns.”

This same year, the McDowells also transfer a piece of property to Avery for $120.

Also that in all deeds George Avery’s sigature is designated with an “X” and the words, “his mark.” It is highly likely that George Avery was never given the opportunity to learn to read or write. And this was the reason that he did not leave written records of where individuals in the cemetery were buried.

August 11, 1922

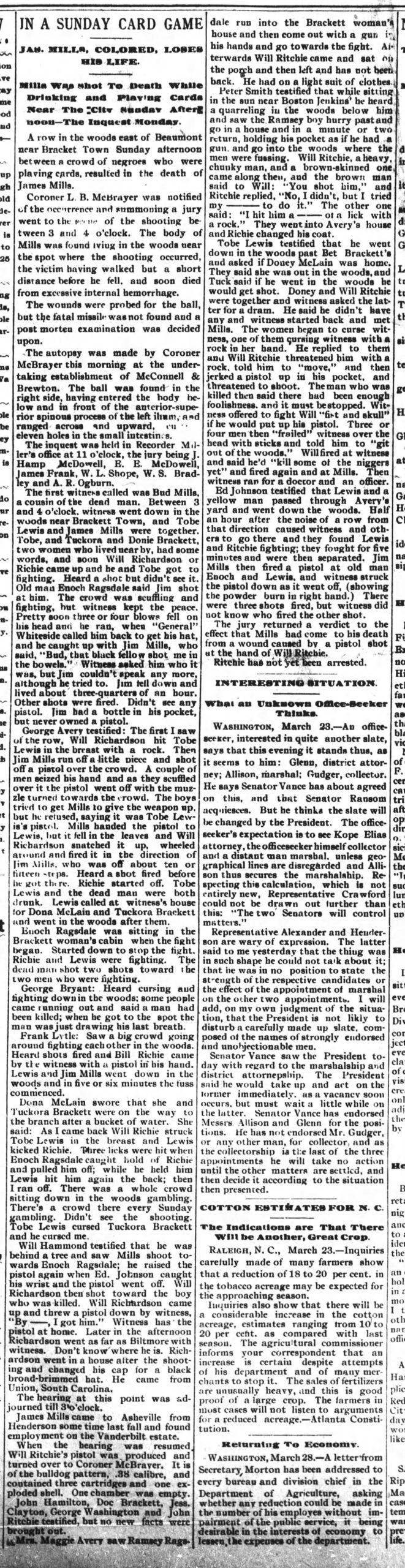

Both Maggie and George Avery were called as witnesses in a 1893 murder trial.

The article from the Asheville Weekly Citizen is, to date, the only direct quote we have attributed to George Avery. He testified:

“The first I saw of the row, Will Richardson hit Tobe Lewis in the breast with a rock. Then Jim Mills run off a little piece and shot off a pistol over the crowd. A couple of men seized his hand and as they scuffled over it the pistol went off with the muzzle turned towards the crowd. The boys tried to get Mills to give the weapon up, but he refused say it was Tobe Lewis’s pistol. Mills handed the pistol to Lewis, but it fell in the leaves and Will Richardson snatched it up, wheeled around and fired it in the direction of Jim Mills, who was off about ten or fifteen steps. Heard a shot fired before he got there. Richie started off. Tobe Lewis and the dead man were both drunk. Lewis called at the witness’s house for Dona McLain and Tuckora Brackett and went in the woods after them.”

Avery continues:

“Enoch Ragsdale was sitting in the Brackett woman’s cabin when the fight began. Started down to stop the fight. Richie and Lewis were fighting. The dead man shot two shots toward the two men who were fighting.”

Asheville Weekly Citizen, March 20, 1893

George’s wife, Maggie, died on March 24, 1913, at 53 years old, and is buried in South Asheville Cemetery.

Her marker reads:

MAGGIE

WIFE OF

GEORGE AVERY

BORN

OCT. 28, 1859

DIED

MAR. 24, 1913

–

I have fought a good fight.

I have finished my course.

I have kept the faith.

In 1914, George Avery married Bessie McAver. [Entry in Buncombe County Register of Deeds.]

In 1920, George, now 74, had opened the home that he owned to his wife Bessie, 36, and her young children, Edward Weaver, 10, and Roberta Weaver, 7. (It is likely that either the person recording Bessie’s last name “McAver” was misread/misheard as “Weaver” or visa versa.) Avery’s adopted son, Richard Houston, 19, and his wife, Lizzie, 18, also live in the house.

The census doesn’t give us much detail about the family’s daily life. However, at 10-years-old Edward is the only person in the household listed as being employed. He is a “laborer” who is “working out.”

[1920 Census, Buncombe County, George Avery]

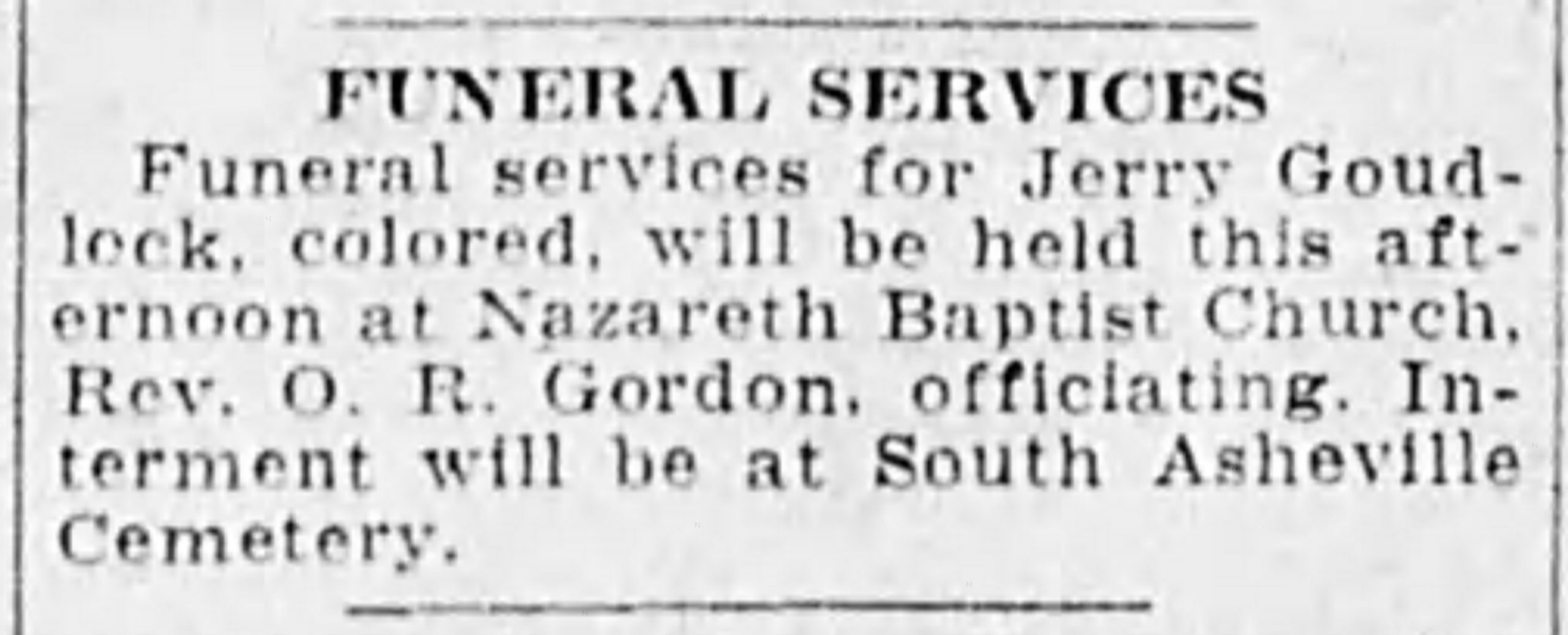

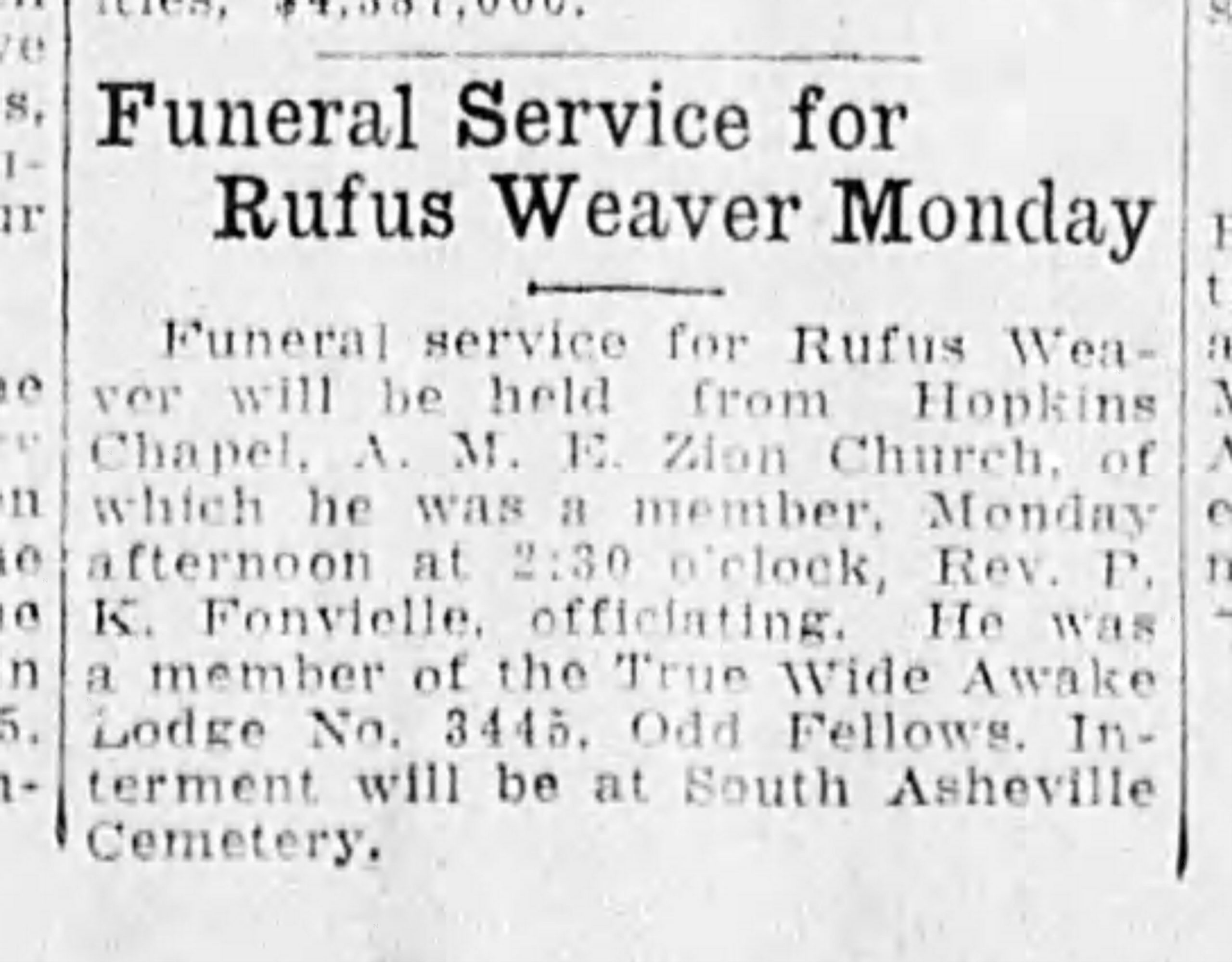

These are the earliest references in the Asheville Citizen that we could find reported on burials at South Asheville Cemetery. It is likely that George Avery was involved in these burials.

Asheville Citizen

November 7, 1923

Asheville Citizen

January 18, 1925

By 1930, an 84-year-old George Avery reports himself as widowed. His son and daughter-in-law and their children continue to live with him.

[1930 Census, Buncombe County, George Avery; Image cropped and spliced to better see column headings.]

It is currently unknown why George Avery was listed as widowed in the 1930 Census and why Bessie Avery was not living in his home as Bessie Avery is the one who submits the “Application for Headstone” for George Avery. Bessie is also listed as his wife on his death certificate.