WNC History: Infidelity may have led to Guastavino’s move here, work on Biltmore, basilica

“The moment her husband died, Frances Guastavino stopped the large clock in the steeple of the big house and for almost 40 years, the big hands told the hour of (Rafael) Guastavino’s death — a few minutes before eight,” wrote Maggie Lauterer in a June 1986 issue of the Asheville Citizen-Times.

The article, “Remembering Guastavino,” delved into the private life of the world-renowned builder, Rafael Guastavino, who revived a Catalan masonry technique of layering thin tiles to produce lightweight and fireproof self-supporting arches, which can be seen in some of America’s most famous landmarks, including Boston Public Library, Grand Central Terminal, Grant’s Tomb, the Great Hall at Ellis Island, Carnegie Hall, the Smithsonian, the U.S. Supreme Court, the Biltmore House, and Asheville’s Basilica of St. Lawrence.

Lauterer collected numerous stories about the builder and his second wife, Francesca, who lived in the Asheville area beginning in 1894. Lauterer centered her article around the couple “who loved each other as lovers do in novels.” While to some, the romance may seem irrelevant to Rafael’s vast architectural accomplishments, it is very possible that Guastavino and his innovative tile techniques may never have arrived in Asheville — or even this country — if not for the builder’s tumultuous private life.

Guastavino was born in 1842 in Valencia, Spain. As a teenager he moved to Barcelona to study architecture. There, Rafael lived with his aunt and uncle and their adopted daughter, Pilar. Not long after 17-year-old Rafael arrived, 16-year-old Pilar became pregnant. The couple immediately married, and their first son, Jose, was born in 1860. Two more sons followed soon after — Ramon in 1861 and Manuel in 1863.

Once achieving the title of “master builder,” Guastavino, with help from family connections, was awarded a high-profile commission – Barcelona’s largest textile factory; his impressive and efficient design launched his career in Spain.

Things at home were not going nearly as well. Rafael had begun a relationship with his sons’ nanny, Paulina Roig. After learning of the affair — which had apparently not been his first — Pilar left Rafael and took the children. While some accounts note that the couple reconciled in 1871 long enough to conceive a fourth son, Rafael Guastavino Jr., recently-discovered family letters indicate that Rafael Jr.’s mother was not Pilar, but the nanny, Paulina. Paulina soon moved in with Rafael and their son, taking the title of “housekeeper” in official records.

This, then, might explain why Rafael took only his youngest son with him to New York in April 1881, and why Paulina traveled with them. (A few months previously, Pilar and her three sons had immigrated to Argentina so that the boys could avoid the Spanish draft.)

These same family letters also indicated that Rafael’s immigration to the United States was motivated, or at least financed, by something perhaps even more sensational than his extra-marital affairs. Apparently, by way of a promissory note scam, Guastavino had pocketed $40,000 (the equivalent of about $400,000 today) to begin anew in New York City.

Guastavino struggled to secure commissions in the U.S. Still, in 1889, he and his son founded the Guastavino Fire Proof Construction Company. And, with the flammability of rare books and archival collections in mind, the firm of McKim, Mead, & White awarded Guastavino’s company its first major contract – seven vaulted ceilings in Boston Public Library. The success of this commission would lead to tile-vaulting projects across the US for the father-son duo.

At home, things continued to be rocky with the women in Rafael’s life. How long Rafael and Paulina’s relationship lasted once they arrived in America is not known, but — after opening an office in Boston — he was romantically linked to at least one local woman. Then, as he traveled back and forth between Boston and New York for work, he fell in love with Francesca Ramirez. Francesca was significantly younger than Rafael, and — because Rafael was still legally married and a devout Catholic — identified herself as his daughter when she moved into the New York City townhouse he shared with his son. It proved a difficult charade to maintain.

At the same time, Guastavino’s professional reputation for beautiful, relatively inexpensive, and high quality tile vaults grew. By the early 1890s, he had been commissioned to install tile work in George Vanderbilt’s Biltmore House in Asheville. Guastavino soon decided to relocate to NC’s mountains, where he could build his own estate near the North Carolina clays used in much of his work.

And moving to North Carolina solved another problem; he and Francesca could stop posing as father and daughter.

In 1894, Rafael — apparently estranged from his three oldest sons — placed advertisements in South American newspapers to try to locate Pilar and confirm if his wife was still living. With no word either way, 51-year-old Rafael married 33-year-old Francesca on September 12, 1894. (The following year, in Argentina’s national census, Pilar, now 56 and still using the surname Guastavino, reported being married for 36 years and having four children.)

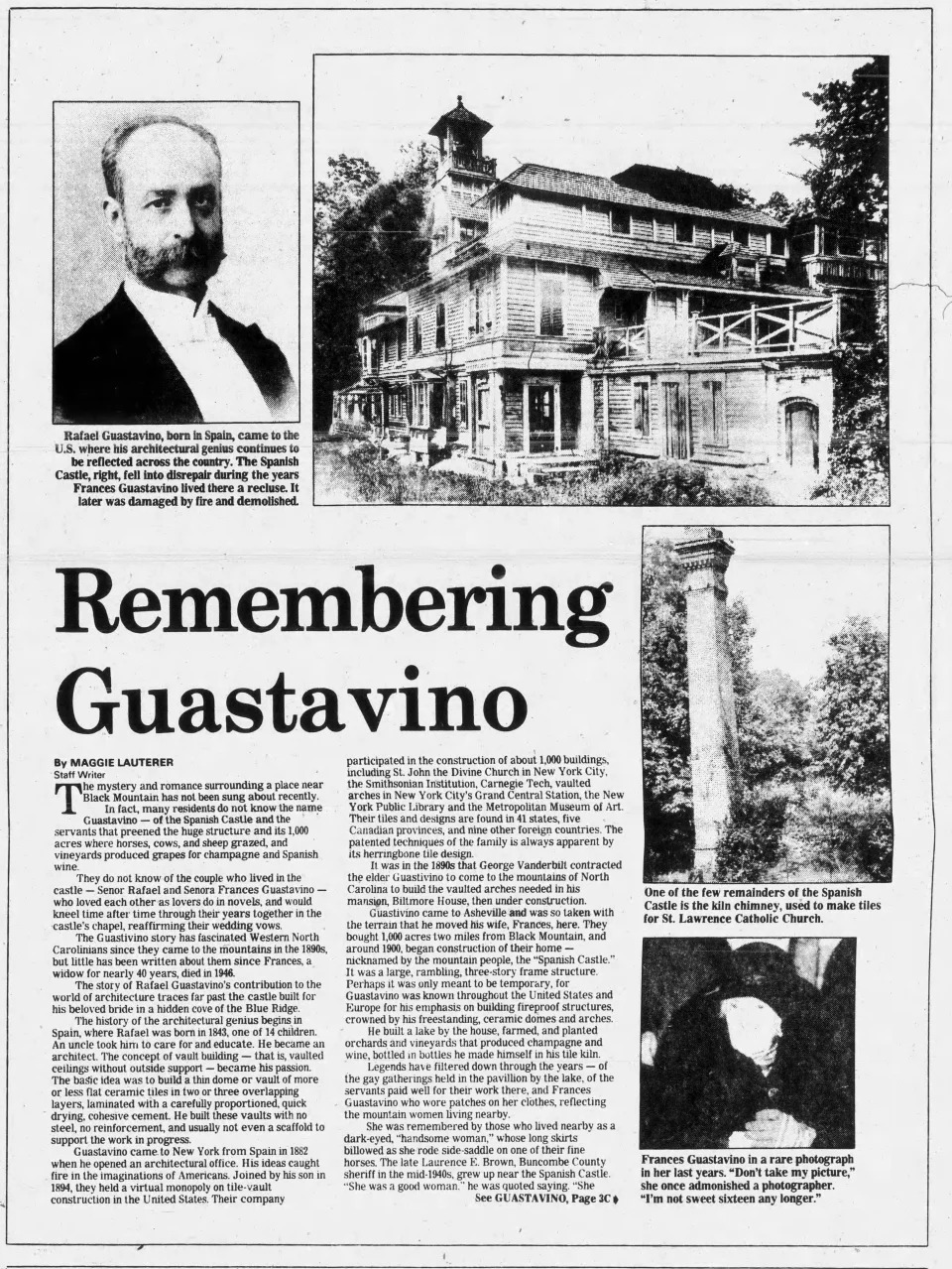

With his new wife, Guastavino built a large home on property he bought in Black Mountain. Known as Rhododendron, Guastavino’s estate was far from typical — for him or for the Black Mountain area. Though known for his fireproof tiles, Guastavino constructed his home from wood. The rambling, three-story, white-washed house contained 25 rooms including a billiard room, bell tower, and chapel.

It was in this chapel that Francesca and Rafael would, as Maggie Lauterer wrote in 1986, “kneel time after time through their years together … reaffirming their wedding vows.”

By 1903, Guastavino, now semi-retired, began working on his passion project – a Catholic Church designed around a large, free-span elliptical dome. He financed most of the Asheville-based project himself and provided much of the tile, which had been fired in kilns at Rhododendron.

As construction on the church neared completion, Rafael became ill and never recovered, dying on Feb. 1, 1908. Francesca was devastated. The widow, once a socialite who hosted lavish dinner parties at Rhododendron, became a recluse, always dressed in black.

“With her beloved husband gone, the senora stayed in the Spanish Castle alone,” Lauterer wrote in concluding the Guastavinos’ love story. “It is said that she sat a plate at her deceased husband’s chair each night for the evening meal, sometimes telling a man servant that her husband may come back someday.”

Rafael Guastavino Jr. oversaw the remaining details of his father’s church, including the installation of an interior vault where the elder Guastavino was interred. The church, now the Basilica of St. Lawrence, was designated a Basilica in 1993.

Though Francesca remained in the Rhododendron house until a few years before her 1946 death, it quickly fell into disrepair. All that remains of the Guastavinos’ home is a brick foundation adjacent to an underground wine cellar – the only portion of the home built using Guastavino’s famous vaulting techniques.

So the questions remain: Would Rafael Guastavino have come to the United States if not for his infidelity? Would he have still settled in Asheville after finishing work on the Biltmore Estate, if not for his desire to leave behind a city that only knew the love of his life as his daughter? What would America’s great public places with their soaring tiled domes and arches look like if Rafael Guastavino’s first wife had never left him?

Anne Chesky is the executive director of the new Asheville Museum of History, which will open the exhibit, “Palaces for the People: Guastavino and America’s Great Public Places,” at the end of October.